A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels — Part 1, the RIN tax

Summary

This is a four-part blog series describing the renewable identification number (RIN) as a tax (this part 1) and a subsidy (part 2) that forces renewables into fuels (part 3), and how this tax-and-subsidize interpretation resolves the apparent contradiction (part 4) at the core of the legal dispute over RINs now in its 10th year. The RIN tax increases the blend cost of refined blendstocks and the RIN subsidy reduces the blend cost of renewable blendstocks. These changes cause the demand for refined blendstocks to decrease and the demand for renewable blendstocks to increase. In the case of the 10% ethanol/gasoline blend sold to consumers, which we are using as an example case, the price of the blended fuel is almost exactly unchanged. The payment of the RIN tax by refiners and the receipt of the RIN subsidy by blenders are tangible transactions whose financial effects are easy to measure and easy to understand. But two other financial effects are intangible, not easy to measure, and not easy to understand – they are the effects on the market prices of the refined blendstock (called BOB) and the blended fuel (called E10). A key for understanding RINs is to recognize that, in competitive markets, these two market prices emerge “automatically” as a consequence of competitive forces in the market rather than by the deliberate action of any individual or single company. Another key is to recognize how competition in the E10 market forces the blender to apply the revenue from its RIN sale as a credit on the effective blend cost of ethanol, and how that causes the RIN tax to cross-subsidize ethanol used as fuel. At the individual refiner and blender level, the RIN has no impact on profitability. At the aggregate market level, there are impacts on the refining and blending industries that requires a different, related analysis. This tax-and-subsidize interpretation provides a sound fundamental framework for making sense of the apparent contradiction at the core of the 9-year dispute over RINs, and for understanding other important subjects like RIN pricing theory.

A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels — Part 1, the RIN tax

In April, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released the latest ruling in the long-running dispute between refiners and EPA over the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). The ruling denied 36 petitions from refiners seeking exemptions to their obligation to blend renewables like ethanol and bio-based diesel into fuels for the 2018 compliance year.

At the core of the dispute are two contradictory premises about Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs). One premise says the RINs system adds cost that hurts a refiners’ profitability. The other says the RINs system does not hurt a refiners’ profitability. These two premises cannot both be true. In this series of blog posts, we probe into the contradiction underlying this long-running dispute.

We begin with this definition:

A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels.

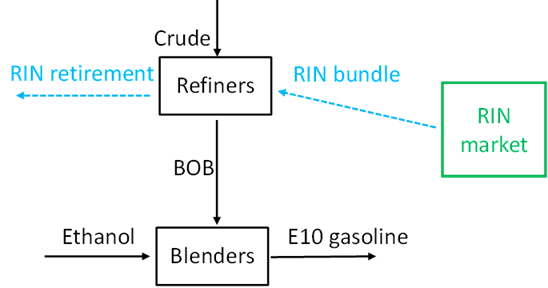

In Figure 1, The black arrows show the process flow for production of E10 which is the 10% ethanol blend we use as gasoline in our cars. Refiners process crude oil into refinery gasoline called BOB which means Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending. Fuel blenders purchase BOB and ethanol, and blend 90% BOB with 10% ethanol to make E10 gasoline for delivery to retail stations.

The blue arrows show the tax aspect of RINs. The refiner buys a RIN bundle, which is like a receipt showing he purchased his quota of RINs. The quota of RINs is set annually by EPA and is called the Renewable Volume Obligation. In RIN retirement, the refiner turns in the receipts to prove the RIN obligation was met. Think of these two steps, the purchase and the retirement of a RIN bundle, as the fulfillment of a tax obligation.

Two camps on how the RIN affects a refiner’s profit

We are now ready for today’s main question — How does the RIN tax affect a refiner’s profit?

There are two camps. Camp A, mostly refiners with some economists, consultants, and politicians, says the RIN tax is an extra cost that reduces refining profit. Camp B, mostly renewable producers with other economists, consultants, and politicians, says the RIN tax is passed through and recaptured in a higher price for the BOB.

Camp A’s view makes sense. A refiner sends real cash out the door to buy RINs whose prices fluctuate wildly with no apparent offsetting revenue. It is a source of large, uncontrollable, highly variable increase in his cost. How can it not affect his profit?

Camp B holds to the “pass-through” theory which says the refiner’s RIN cost is recaptured in a higher BOB price, and this is consistent with economic theory and supported by empirical analysis of market prices.

So this dispute features a concrete, sensible viewpoint (held by Camp A) against an intangible, theoretical viewpoint (held by Camp B).

Which camp is right?

The disagreement is about economics, so should be resolvable using data, empirical analysis, and economic science like the law of supply and demand. But we must also be able to grasp and explain how the solution conforms with what we plainly see happening in the real world.

A big problem is that pass-through cannot be measured directly.

A big problem is that pass-through cannot be measured directly.

That would require measuring the difference between the actual BOB price and what the BOB price would have been with no RIN system. But the “would have been” price is not measurable. Consequently, the approach for empirical analysis has taken an indirect route by analyzing price differences between similar fuels which are affected, and not affected, by the RIN scheme; for example, by comparing the prices of New York Harbor RBOB (Reformulated BOB which is a specific type of BOB) gasoline, which is affected, with Rotterdam EuroBOB gasoline, which is not, or the price of U.S. Gulf Coast ultra- low-sulfur diesel, which is affected, and jet fuel, which is not.

The empirical analyses have been done and provide convincing evidence for Camp B’s claim. But it is indirect evidence that has caveats, is hard to explain and easy to dismiss as too intangible, especially when compared to hard cash going out the door.

Tax incidence theory

The economic theory behind RIN pass-through is known as “tax incidence theory” which deals with how a tax burden is divided between buyers and sellers. To illustrate, suppose the RIN bundle in Figure 1 is a simple sales tax, so-much per gallon, paid to the government by the refiner. Tax incidence theory says that, because the tax affects all refiners in the market, it will be passed through into the market price of BOB until the higher BOB price reduces total BOB demand in that market. At that point, there will be pressure driving the market price to a new equilibrium where the tax burden is shared fractionally between the refiner and blender. This fractional sharing is common in many markets. But we know that in the fuels market, it takes a huge percentage price increase to cause even 1% reduction in total market demand. So the economic theory implies that, for fuels, the RIN tax will get almost fully (95% plus) passed through to the blender.

This argument from economic theory makes sense, but it is also intangible and not easily understood and accepted.

A nine-year legal/political battle

Legal battles over RINs have been triggered by various market issues.

But, regardless of the issue, the debate is always drawn back to this core disagreement over pass-through and how RINs affect a refiner’s profit.

regardless of the issue, the debate is always drawn back to this core disagreement over pass-through

For example, the United States Court of Appeals decision of August 30, 2019 addressed proposals to re-assign the RIN tax obligation to blenders or other entities in the fuel supply chain, instead of refiners. That decision states Camp A’s view as follows:

“At the root of petitioners’ claim is a single premise: that the current point of obligation misaligns incentives by requiring those who refine fossil fuel, but not those who blend it, to meet the RFS program’s annual standards. In petitioners’ view, this misalignment forces refiners to purchase RINs to satisfy their RFS obligations, jacking up their costs, while giving windfall profits to blenders, who produce (but don’t consume) RINs.”

U.S Court of Appeals, Aug 30, 2019

The same court decision states Camp B’s contrary premise as follows:

“The problem with this argument, however, is that EPA reasonably explained why, in its view, there is no misalignment in the RFS program. According to EPA, refiners recover the cost of the RINs they purchase by passing that cost along in the form of higher prices for the petroleum based fuels they produce . . . It grounded that conclusion in studies and data in the record.”

U.S Court of Appeals, Aug 30, 2019

As another example, the April 7, 2022 EPA denial of small refiner exemptions deals with a different issue, whether small refiners face disproportionate economic harm from the RIN tax. The denial followed a series of previous rulings and decisions on that issue. It also drew the debate back toward the pass-through theory, stating Camp A’s comments on the topic as follows:

“These comments articulate the following general themes:

(a) Small refineries face unique challenges that prevent them from achieving RIN cost pass-through and EPA must consider their specific circumstances

. . . .”

EPA, Apr 7, 2022

and Camp B’s view is stated as follows:

“We find that all obligated parties recover the cost of acquiring RINs by selling the gasoline and diesel fuel they produce at the market price, which reflects these RIN costs (RIN cost pass-through)”.

EPA Apr 7, 2022

Whatever the legal issue, the focus gets drawn like a magnet to this core disagreement on RIN tax pass-through.

Moving back even further in time, we see Camp A’s view expressed concisely in Carl Icahn’s open letter to EPA Aug 19, 2016, stating

“A defense made is that refiners are not hurt because they are passing on their cost of RINs by raising prices to the blenders. This is absurd and the obvious proof that it is not happening is the billions of dollars currently being lost by refiners”.

Carl Icahn, Aug 19, 2016

That takes us back seven years. And, as we will see, the direction of this same debate is foreshadowed in publications going back as far as 2013.

Growing acceptance of the pass-through theory

Over time, the tide has turned toward acceptance of the pass-through theory. Many refiners state on the record they agree with the pass-through theory. And the statement quoted above, that “small refineries face unique challenges that prevent them from achieving RIN cost pass through”, suggests the small refiners’ situation is now seen as an exception, where pass-through is the rule.

Recommendation

Anyone with a stake in RINs pricing and economics should get Hoekstra Research Report 10 which includes the Hoekstra ATTRACTOR spreadsheet spreadsheet that accurately calculates D4T, the theoretical RIN price, tracks it versus quoted market prices, and predicts how RIN prices will change with the variables that affect them. Why not send a purchase order today?

George Hoekstra george.hoekstra@hoekstratrading.com +1 630 330-8159

Anyone with a stake in RINs pricing and economics should get Hoekstra Research Report 10

The next step

We started this with a definition: A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels. This Part 1 of the series addressed the RIN as a tax and focused on pass-through as the core issue in the disagreement over the tax aspect of RINs.

The next step is to see how the RIN works as a subsidy

The next step is to see how the RIN works as a subsidy, and that is Part 2 of this series. The subsidy aspect contributes equally, but has been a less visible aspect, and less analyzed than the tax aspect of this disagreement (or is it a misunderstanding?).

George Hoekstra george.hoekstra@hoekstratrading.com +1 630 330-8159