A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuel Part 3 – How do RINs force renewables into fuel?

Summary

This is a four-part blog series describing the renewable identification number (RIN) as a tax (part 1) and a subsidy (part 2) that forces renewables into fuels (this part 3), and how this tax-and-subsidize interpretation resolves the apparent contradiction (part 4) at the core of the legal dispute over RINs now in its 10th year. The RIN tax increases the blend cost of refined blendstocks and the RIN subsidy reduces the blend cost of renewable blendstocks. These changes cause the demand for refined blendstocks to decrease and the demand for renewable blendstocks to increase. In the case of the 10% ethanol/gasoline blend sold to consumers, which we are using as an example case, the price of the blended fuel is almost exactly unchanged. The payment of the RIN tax by refiners and the receipt of the RIN subsidy by blenders are tangible transactions whose financial effects are easy to measure and easy to understand. But two other financial effects are intangible, not easy to measure, and not easy to understand – they are the effects on the market prices of the refined blendstock (called BOB) and the blended fuel (called E10). A key for understanding RINs is to recognize that, in competitive markets, these two market prices emerge “automatically” as a consequence of competitive forces in the market rather than by the deliberate action of any individual or single company. Another key is to recognize how competition in the E10 market forces the blender to apply the revenue from its RIN sale as a credit on the effective blend cost of ethanol, and how that causes the RIN tax to cross-subsidize ethanol used as fuel. At the individual refiner and blender level, the RIN has no impact on profitability. At the aggregate market level, there are impacts on the refining and blending industries that requires a different, related analysis. This tax-and-subsidize interpretation provides a sound fundamental framework for making sense of the apparent contradiction at the core of the 9-year dispute over RINs, and for understanding other important subjects like RIN pricing theory.

A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuel Part 3 – How do RINs force renewables into fuel?

Refiners and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have locked horns in a dispute over Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) now in its 10th year. The dispute stems from contradictory premises about how RINs affect the profits of refiners and blenders who produce ground transportation fuels sold in the USA.

This is the third in a four-part series examining the fundamentals of how RINs work using the definition: A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels.

We are considering the example case of E10 which is the 10% ethanol, 90% BOB (blendstock for oxygenate blending) gasoline we use to fuel our cars, SUVs and pickups. Part 1 focused on the tax aspect of the RIN and how that affects a refiner’s profit. One camp, which we call Camp A, says it hurts a refiner’s profit and the other camp, which we call Camp B, says it doesn’t. Part 2 focused on the subsidy aspect of the RIN and how that affects the blender’s profit. Camp A says it is a windfall profit for blender and Camp B says it isn’t.

A RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels.

Part 2 also told the stories of blender-retailers Casey’s General Stores and Murphy USA who first thought RIN revenues were a windfall for them, then did about-faces and decided they weren’t.

In both parts 1 and 2 we emphasized there is a tangible and an intangible part to the profit impact of RINs. From the refiner’s perspective, the tangible part is paying cash to acquire a RIN, and from the blender’s perspective, it is receiving cash from selling a RIN. The intangible part, also seen by both sides, is how the RIN affects the price they pay, or receive, for BOB, which is not directly measurable and, for that reason, has been the focal point of the disagreements (or are they misunderstandings?). In today’s part 3 of the series, we focus on the blending and sale of finished E10 gasoline and answer two questions about that: 1) How do RINs force renewables into fuels? and 2) Does the RIN system increase the price of E10 to consumers?

The short answer to Question 2 is no. That seems surprising because we are told by Camp B the RIN tax gets passed through from refiner to blender in the form of a higher price for BOB, and it makes sense then the tax should also pass through from blender to consumer, increasing the price of E10. And the RIN tax does pass through that way.

But here is the twist: The RIN subsidy also passes through to the consumer in the form of a lower effective cost for the ethanol component of the E10 blend. And the tax on the BOB and the subsidy on the ethanol almost exactly cancel, leaving the E10 price almost exactly unchanged.

here is the twist: The RIN subsidy also passes through to the consumer in the form of a lower effective cost for the ethanol component of the E10 blend.

This is called a cross-subsidy.

In a cross-subsidy, an artificially inflated price for one component subsidizes another component. An example is when professional members of an industry society pay an inflated membership fee that cross-subsidizes a discount for student memberships.

In a cross-subsidy, an artificially inflated price for one component subsidizes another component.

Similarly, the RIN tax and the RIN subsidy almost exactly cancel and the cost of E10 is almost exactly the same as what it would be without the RIN system or at any other RIN price (the almost exactly part is a wrinkle we will iron out later).

The RIN system deliberately distorts the effective costs of fuel components like BOB (upward) and ethanol (downward) such that when they are blended together the inflated cost of BOB cross-subsidizes a discount on ethanol. The discount on ethanol, which is commonly called the “RIN discount”, reduces the effective cost of ethanol when blended into gasoline.

The RIN Discount

The new thing here is the blender is counting its RIN revenue as a credit (a negative cost) in figuring its cost of E10. What compels it to do that instead of just keeping the RIN revenue as profit? It is forced by competition in the E10 market. All E10 blenders get the same per-gallon RIN revenue when they blend ethanol into fuel. The blenders cannot keep it as a windfall because, if they try, their competitors can and will increase their profits by lowering their E10 price and stealing market share from them. This price competition continues, forcing the market price of E10 down to a new equilibrium where the common RIN windfall has been squeezed out of everyone.

Quantifying the RIN discount

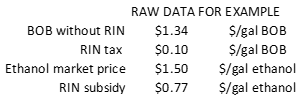

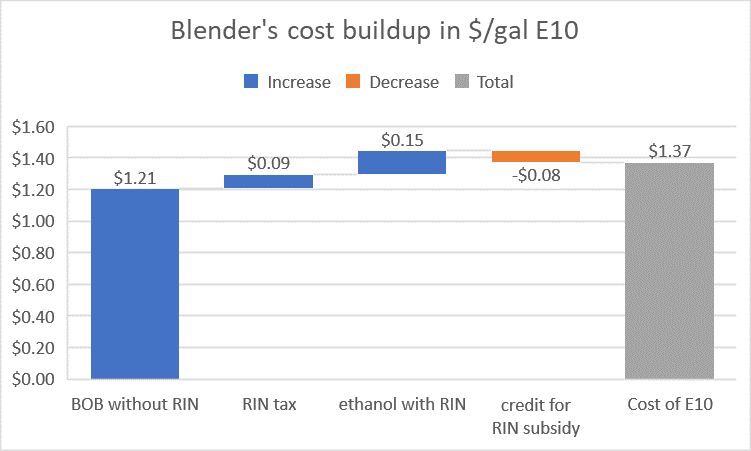

To quantify the RIN discount and cross-subsidy, let’s use an example from pages 41-44 of EPA’s April 2022 Denial of Petitions for RFS Small Refinery Exemptions. Consider a blender making a gallon of E10, which is 90% BOB plus10% ethanol, on Dec. 30, 2020, when the market price of BOB was $1.34/gal of BOB without a RIN and $1.44/gal of BOB with a passed-through RIN, the cost of the RIN bundle (RIN tax) was $0.10/gal of BOB, the market price of ethanol was $1.50/gal of ethanol, and the D6 RIN price (RIN subsidy) was $0.77/gal of ethanol:

They calculate their cost of the blend to be the weighted sum of the costs of the two components they buy on the market; that is 0.9 times their cost for BOB plus 0.1 times their cost for ethanol. If you multiply the first two numbers above by 0.9 and the second two numbers by 0.1, you get the following buildup of the blender’s blend cost, now in units of $/gal E10:

The blenders cannot keep it as a windfall because, if they try, their competitors can and will increase their profits by lowering their E10 price and stealing market share from them.

The squeezed-out windfall accrues as a credit (negative cost) on the blender’s cost of ethanol because the ethanol is its source (via the RIN that was originally attached to it), hence the blender’s RIN revenue is transformed into a discount on the cost of ethanol which subsidizes the use of ethanol in the blend. At the new equilibrium E10 price, the effective cost of the ethanol component is the market price of ethanol minus the value of the RIN subsidy. And that is the answer to question 1. The RIN attached to the ethanol enables a discount on the blend, and competition in the E10 market forces the blender to apply that discount to the cost of their ethanol component which subsidizes ethanol and increases the demand for ethanol, that is, it forces ethanol into fuels which is exactly what the RIN system was designed to do.

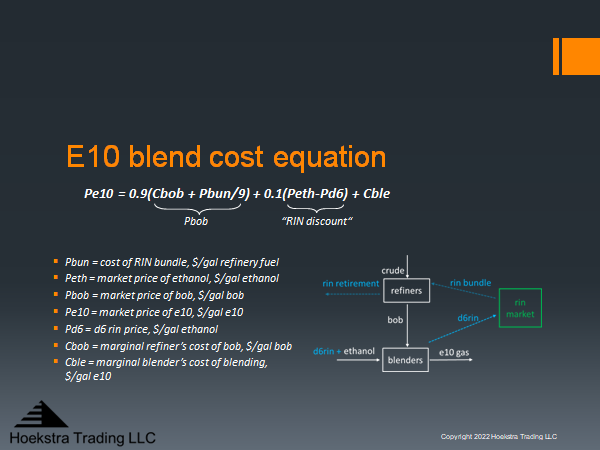

With the perspective of the tax-subsidize interpretation, it is possible to put this into the form of a general equation for the wholesale market price of E10 that shows explicitly the pass-through of the RIN tax in the market price of BOB and the discount on the blend cost of ethanol by the RIN subsidy, as shown below:

Source: Hoekstra Trading LLC

This was derived by writing down the profit equations for the refiner and blender, doing a money balance, and applying the conditions that describe fully-competitive markets for BOB and E10.

The cross-subsidy works

Compared to the pass-through of the RIN tax, the RIN subsidy has drawn little attention in the long debate. It appears in academic articles, and then when the rulings and decisions come out the subsidy is explained along with how the tax and subsidy work together without affecting the price of E10. Both economic theory and actual data say this two-pronged system does work as designed. When RIN prices go up or down, BOB prices go up or down, the effective cost of renewables blended to fuels goes down or up, by corresponding amounts, and, in the case of E10, the blended product price is almost exactly unchanged.

The law of supply and demand performs this work via the prices of BOB, E10, and the D6 RIN, which are market prices, not set directly by any single person or company, but that emerge from competition among buyers and sellers in the markets for BOB, E10, and RINs.

This non-intuitive outcome has been puzzling market participants in both camps for years.

Murphy USA example

Murphy USA is a large blender and gasoline chain owner. In a 2021 earnings conference call, Andrew Clyde, Murphy’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) explained how the tax-and-subsidize system works in reply to an analyst’s question on how RINs affected Murphy’s reported fuel profit margins in the first quarter of 2021 in which Murphy beat its earnings estimates:

Murphy CEO —“. . . we do have a couple of headlines that said our beat was because of RINs. And the reality is RINs and RIN prices are immaterial to our business. Historically, and you can look back over the last 3-year annual results, we’ve made $0.02 to $0.03 per gallon on product supply and wholesale net of RINs. And so during the quarter on the average, we generated about the equivalent of $0.07 a gallon per RIN, but net of the negative spot to rack margins of $0.04, we netted a little bit over $0.03, . . . so call it sort of $0.03 net of the supply margin net of RINs.”

The last sentence states the point of today’s blog. Let’s examine it closely in light of our definition of RINs:

“And so during the quarter on the average, we generated about the equivalent of $0.07 a gallon per RIN,”

Andrew Clyde – President, CEO & Director, Murphy USA

The 7 cents per gallon is the revenue from RIN sales which is the RIN subsidy.

“but net of the negative spot to rack margins of $0.04,”

Andrew Clyde – President, CEO & Director, Murphy USA

“ . . . negative spot to rack margin” refers to the wholesale market price of E10 minus the weighted sum of the market prices of BOB and ethanol. This difference is negative because the market price of BOB includes the (passed-through) RIN tax. Because he has picked up the passed-through RIN tax, if Murphy doesn’t treat the 7 cent subsidy as a credit on the cost of the blend, Murphy would lose 4 cents per gallon blending and selling E10!

“we netted a little bit over $0.03,”

Andrew Clyde – President, CEO & Director, Murphy USA

When Murphy counts the 7 cent subsidy as a credit on the cost of the blend, that overcomes the 4 cent negative spot to rack margin and leaves 3 cents per gallon profit to be made by blending and selling E10 at its wholesale market price. That’s better than nothing, so Murphy does it. The RIN subsidy has given Murphy the necessary incentive to overcome the tax and force ethanol into fuel.

“ . . .so call it sort of $0.03 net of the supply margin net of RINs.”

Andrew Clyde – President, CEO & Director, Murphy USA

The 7 cent tax, built into the market price of BOB, and the 7 cent subsidy that came attached to the RIN, cancel; and Murphy’s underlying economic profit is $0.03 per gallon, plus or minus, regardless of RINs.

In Part 1, we told the same story about Casey’s General Stores who told analysts for years their RIN revenue added to fuel margin, then did an about face in 2018 and came to the same conclusion as Murphy.

A clever market manipulation?

Looked at in the light of the tax-subsidize interpretation, this is a clever scheme. The RIN tax and subsidy get “blended” together, along with the streams that carry them, in a cross-subsidy that forces ethanol into fuel while leaving the refiner’s profit, the blender’s profit, and the price of E10 almost exactly unchanged. In the case of higher ethanol blends like E15 or E85, the cost of the blended fuel goes down when RIN price goes up, which is evident from how the weighting factors (%ethanol and %BOB) affect the weighted sum in the blend cost calculation explained above.

This tax-subsidize interpretation suggests that, at the individual refiner’s level, there is no impact on a refiner’s profits. That is not to say, however, there is no impact on the refining industry. That impact must be analyzed at the aggregate market level, which is a related, but different analysis.

Recommendation

Anyone with a stake in RINs pricing and economics should get Hoekstra Research Report 10 which includes the Hoekstra ATTRACTOR spreadsheet spreadsheet that accurately calculates D4T, the theoretical RIN price, tracks it versus quoted market prices, and predicts how RIN prices will change with the variables that affect them. Why not send a purchase order today?

George Hoekstra george.hoekstra@hoekstratrading.com +1 630 330-8159

Anyone with a stake in RINs pricing and economics should get Hoekstra Research Report 10

The next step

Having shown how RINs work as a tax, a subsidy, and a cross-subsidy that forces renewables into fuels, the next step is to wrap up this series in Part 4 by seeing how this tax-subsidize-force interpretation illuminates some high profile disagreements (or are they misunderstandings?) that have gone all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States.

George Hoekstra george.hoekstra@hoekstratrading.com +1 630 330-8159