The New Game of Renewable Fuels Part 3 – WHY Are The RFS Mandates Nested?

The spectacular increase in the price of the D6 Renewable Identification Number (RIN) in 2013 was one of the most extreme moves in the history of major commodity trading.

Read the other blogs in this series, The New Game of Renewable Fuels:

- Part 1-The Rules Of The Game

- Part 2-Three Basic Principles

- Part 3-WHY Are The Mandates Nested?

- Part 4-On The Brink

- Part 5-Changing Factors

- Part 6-Playing By The Rules

RINs are the environmental credits used to certify compliance with the U.S. federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). The 100-fold (10,000%) spike in the D6 RIN — from a low of 1 cent in 2012 to more than 1 dollar in July 2013 — meant U.S. refiners and petroleum fuel importers, who naturally tend to be short RINs, suddenly faced unexpected RIN costs totaling $14 billion per year, a figure that exceeded the total cost of their payrolls.

That 10,000% price spike, which we call the “Big Bang”, occurred because ethanol use in gasoline, which had been increasing steadily toward 10%, reached the 10% maximum that can be blended into E10 gasoline (a level also known as the “blend wall”).

The U.S. gasoline pool was then 130 billion gallons/year. Ten percent of that is 13.0 billion gallons of ethanol/year. The government was now mandating that 13.8 billion gallons of ethanol be blended into a U.S. gasoline pool that could only hold 13.0 billion gallons of ethanol. This created a dilemma, like when you want to pour more cream into your coffee after it has already reached the brim and no more will fit.

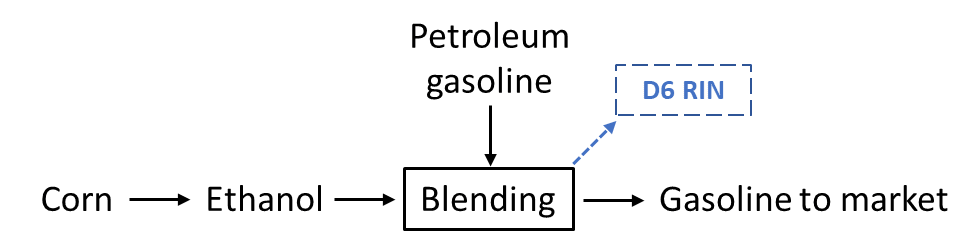

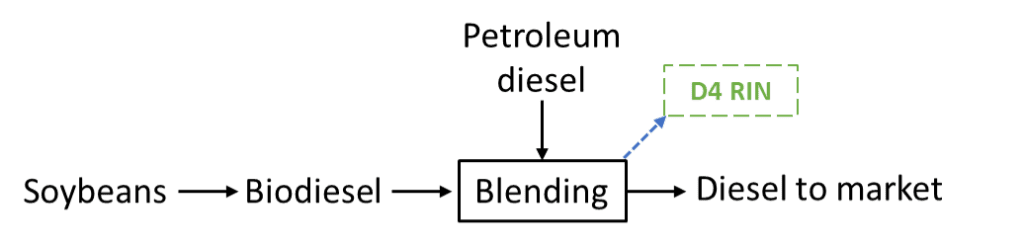

RINs come in different categories with different code names. The D6 RIN applies to the blending of corn-derived ethanol into gasoline (see Figure 1 above). The D4 RIN applies to the blending of biodiesel into petroleum diesel. Biodiesel is made predominantly from soybean oil (see Figure 2 below).

Most gasoline consumers are aware that 10% corn-based ethanol is being blended into our gasoline today. But what exactly is “bio-based diesel”? Let’s take a quick digression into the world of chemistry.

Think of a molecule of soybean oil as being like a three-legged stool. If you (chemically) chop the legs off the stool, the legs make perfectly good diesel fuel. That is what bio-based diesel producers do. They chemically chop the three legs off soybean oil molecules (called triglycerides) to make three molecules of bio-based diesel, along with some byproducts.

And lots of that bio-based diesel, whether you know it or not, is being blended into our diesel fuel today. In fact, 60% of the diesel fuel being consumed in California is made from soybeans or other bio-based feedstocks.

Returning now to the 2013 D6 RIN dilemma — how could refiners and gasoline importers fit 13.8 billion gallons of ethanol into an E10 gasoline pool that will only hold 13.0 billion gallons of ethanol?

There were 3 ways out of the dilemma.

One way was to sue the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to force a reduction of the 13.8 billion gallon mandate. That was tried and failed.

The second way was to replace some fraction of E10 gasoline with E85 gasoline, which uses a higher than 10% ethanol blend ratio. That would enable fitting more ethanol into the fixed-volume 130 billion gallon U.S. gasoline pool. That solution (which, incidentally, was the intended solution EPA was trying to force) did not happened because of insufficient consumer demand for E85.

The third solution was to cover the D6 RIN supply shortage by producing additional D4 RINs which would substitute for the missing D6 RINs. That could be done by producing extra bio-based diesel. This D4-for-D6 substitution solution, which was completely overlooked by the market at the time, is what happened. And a necessary implication was the D6 RIN price snapped up by 10,000% to equal the D4 RIN price, shocking an unsuspecting market.

The substitution solution

The overlooked, non-intuitive D4-for-D6 substitution solution was a logical outcome of the nested structure of the biofuel mandates. How it happened requires some explanation. Ethanol and bio-based diesel are two of four categories of biofuels subject to RFS mandates. But the four mandates are not independent. They are nested.

The mandates are not independent. They are nested.

Two independent mandates are enclosed within a third broader mandate which is in turn enclosed within the broadest mandate.

If you take a basic training program on the rules of the RFS, you will certainly learn about this nested structure. But those training programs do not ask, let alone answer, a critical, basic question:

Why are the mandates nested?

Why are the mandates nested?

and that question leads naturally to a related question, what does the nested structure mean for the behavior of the RIN price control system?

My short answers are:

- The mandates are nested because nesting allows some categories of biofuels and their RINs to substitute for other categories in certain situations.

- The possibility of RIN substitution means the RIN prices are inter-dependent.

The RIN prices are inter-dependent

In 2012, during the run-up to the Big Bang, the impending collision with the blend wall was well understood, well publicized and anticipated by the market. But the substitution solution, accompanied by its inevitable skyrocketing D6 RIN price, was not. It came as a huge shock when it hit. That is because the market did not understand why the mandates are nested, or what that implied for the blend wall dilemma, that is to say, they did not understand the rules of the game they were actually playing.

More specifically, they were fixated on D6 RIN and ethanol and unaware of, or not attending to the interdependence with the D4 RIN.

The substitution solution launched a whole new branch of renewable fuels history that had many interesting implications for the renewable fuels story. One of those is that production of bio-based diesel is a very costly way to comply with the RFS mandates. The process of growing soybeans, crushing them to make soybean oil and chopping the legs off soybean oil to get bio-based diesel costs more than double the cost of producing diesel by distilling it out of crude oil you pump out of the ground. For example, in April, 2023, it was costing $5/gal to produce diesel from soybean oil and $2/gal to produce its perfect substitute from crude oil.

The costly soybean oil path is happening only because the $3/gal difference is being covered by subsidies.

But for now, we will table the implications of the substitution solution. Today’s key point is that the Big Bang is one example of the overwhelming evidence supporting the bold claim I made in Part 2 of this series, that the RIN market operates with an incomplete understanding of the rules of the game being played. Next week’s blog will give another such example.

Recommendations

1) Get Hoekstra Research Report 10

Hoekstra Trading clients use the ATTRACTOR spreadsheet to compare theoretical and market RIN prices, analyze departures from theoretical value, and identify trading opportunities on the premise RIN market prices will be attracted toward their fundamental economic values.

Get the Attractor spreadsheet, it is included with Hoekstra Research Report 10 and is available to anyone at negligible cost.