Breaking the Chains Part 1 – How the Tier 3 ultra-low sulfur gasoline mandate is handcuffing U.S. gasoline production

A commodity that’s gone straight up

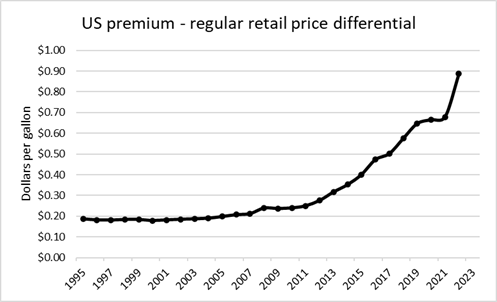

While the stock market, crude oil, fuel prices, and cryptocurrencies have gone up and down wildly, the price of one important commodity has been quietly going straight up for years. That commodity is octane. Figure 1 shows that the retail price of octane, measured by the difference between the pump prices of premium gasoline and regular gasoline, has gone straight up for 10 years. Prior to 2007, that difference had been rock steady for decades and never more than 20 cents per gallon. From 2007 to 2012, it crept up to 28 cents per gallon, and then took off on a steady 10-year rise to 90 cents per gallon in 2022.

Octane is a measure of a gasoline’s resistance to pre-ignition during compression in an engine cylinder. We call it an important commodity because it is the primary yardstick of gasoline quality and price. Retail gasoline is classified by its octane rating: regular gasoline has an octane rating of 87 and premium gasoline has an octane rating of 91 to 93. In the United States, the posted gasoline octane rating is the average of the octane measured two different ways, the Research Octane Number (RON) and the Motor Octane Number (MON). That average is called the Anti-Knock Index (AKI) which is the octane number we see posted on the pump. And as most drivers know, higher octane means higher price per gallon.

Increased octane demand

Demand for premium gasoline has increased in the U.S., from under 9% of total gasoline sales in 2008 to 13% in 2022. Reasons include:

- More car owner’s manuals say premium is recommended or required

- Turbocharged vehicles are growing in market share and they require premium

- Car makers want more high compression engines and they need higher octane fuel

- Today’s premium buyer is less price-conscious than before

Today, we have a totally different picture on octane demand and price than in the past. There has been a fundamental change in the octane market. The retail market is now demand-driven, versus cost-driven as in the past. This change is also seen in the incredibly high variation in regional premium-to-regular price differentials across the US; Figure 1 is showing the U.S. average value. Local values are six times higher in some regions of the US than in others.

So higher octane demand is part of this story. What about octane supply?

Tightened octane supply

Looking now at the supply side of the octane ledger, the cost of octane production has been increasing. In a refinery, a process called catalytic reforming is used to increase the octane of gasoline. This process causes a loss of gasoline volume, and that volume loss is the biggest cost of increasing octane. The refining cost to increase the octane of 1 barrel of gasoline by 1 octane number is about $1.50 per octane-barrel, a number that varies across refineries and with changing crude oil and gasoline prices. Generally, the higher the price of crude oil and gasoline, the higher the cost to increase gasoline octane.

Other factors have reduced U.S. octane supply including:

- The U.S. has been exporting 700,000 barrels/day of gasoline which reduces domestic supply.

- Increased use of (high-octane) ethanol in gasoline during 2006 to 2013 discouraged investment in refinery octane supply capacity.

- Increased demand for petrochemicals has increased competition for the same molecules that contribute most to the octane of gasoline, which are aromatics and olefins.

Tier 3 ultra-low sulfur gasoline

Another big factor affecting octane supply has been lurking in the shadows the last few years. That is the new Tier 3 gasoline sulfur specification which is today causing octane destruction in North American refineries.

The EPA’s Tier 3 gasoline sulfur standard applies to all refiners and importers who deliver gasoline to the U.S. market. It was enacted in 2014 with initial phase-in beginning in 2017 and full implementation in 2020. It requires that gasoline must contain no more than 10 parts per million (ppm) sulfur on an annual average basis, and no more than 80 ppm sulfur on a per gallon basis, beginning January 1, 2017. The standard applies to each refinery and each importer.

There were special compliance rules for small refiners that applied during the six-year Tier 3 phase-in period which allowed small refiners to delay compliance until 2020. And other phase-in rules allowed most large refiners to also delay compliance to 2020. Consequently, the effective Tier 3 compliance date was Jan 1, 2020. Then the Covid-19 lock-downs had refineries operating at low utilization rates through 2020 and until mid-2021, during which it was easy to meet the 10 ppm sulfur specification. Only in 2022 have refiners been challenged, for the first time, to meet this difficult new gasoline sulfur specification continuously while running at full speed.

The octane-sulfur squeeze

What is the linkage between the Tier 3 ultra-low sulfur gasoline mandate and octane supply? To answer this we must focus on a part of a refinery called the fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) process train. In most U.S. refineries, the fluid catalytic cracker is the main refining unit for converting low value heavy oils into gasoline and diesel. It produces FCC gasoline, which is the largest single component of the U.S. gasoline pool and one of the most valuable streams in the refinery. FCC gasoline contains from 200 to as much as 5000 ppm sulfur and is responsible for 98% of the sulfur in the gasoline pool. To meet the 10 ppm sulfur gasoline mandate requires removing 99% of the sulfur from this stream. This is done in a refining unit called the FCC gasoline desulfurizer.

Desulfurizing refinery streams is nothing new for refiners. But when the stream you’re desulfurizing is FCC gasoline, there is a twist

Desulfurizing refinery streams is nothing new for refiners. But when the stream you’re desulfurizing is FCC gasoline, there is a twist – because, while desulfurizing, you simultaneously reduce the stream’s octane which is what makes the FCC gasoline valuable. The harder you desulfurize, the more octane you destroy. And when you try to remove the last traces of sulfur, to 10 ppm, octane destruction starts going exponential. That trade-off is the octane-sulfur squeeze.

At this point, it is important to know that a catalytic reformer, a fluid catalytic cracker, and an FCC gasoline desulfurizer are chemical reactors. They don’t just separate the chemical soup that is oil into its component molecules, they do chemical reactions that change the molecules themselves.

For example, a fluid catalytic cracker is a chemical reactor that cracks big molecules into smaller ones, making 2 valuable gasoline molecules out of 1 otherwise worthless big molecule. And the desulfurizer removes the sulfur atom from the sulfur-containing gasoline molecule to produce a valuable sulfur-free gasoline molecule and hydrogen sulfide which is then converted at the refinery to valuable elemental sulfur instead of releasing the sulfur to the air as sulfur dioxide through our tailpipes.

And when you hear about the “crack spread”, which is the difference in value of fuel products versus crude oil, a fluid catalytic cracker makes money on the crack spread by cracking otherwise worthless big crude oil molecules into valuable gasoline molecules not originally present in the crude.

a fluid catalytic cracker makes money on the crack spread by cracking otherwise worthless big crude oil molecules into valuable gasoline molecules not originally present in the crude.

In most U.S. refineries, the fluid catalytic cracker is responsible for most of the refinery’s gasoline production and profitability. And the FCC gasoline desulfurizer is responsible for making that FCC’s gasoline marketable in the U.S. as clean, ultra-low sulfur Tier 3 gasoline.

20 years ago, when we started taking sulfur out of gasoline in the U.S., refiners started building these FCC gasoline desulfurizers. Today, 200 of them exist in refineries around the world, and more keep getting built. The way most U.S. refineries are meeting the new 10 ppm sulfur mandate today is by turning up the heat on their FCC gasoline desulfurizers. And here is the last bit of chemistry for today’s blog— when you turn up the heat, you accelerate a side reaction that converts high octane olefins into low octane paraffins. It’s an undesirable side reaction because olefins have octane around 100 and paraffins have octane around 20. This reaction of olefins to form paraffins is how FCC gasoline desulfurizers destroy octane.

At some U.S. refineries, FCC gasoline loses over 6 AKI octane when desulfurized, that’s equal to the difference between premium and regular gasoline.

At some U.S. refineries, FCC gasoline loses 6 AKI octane when desulfurized, that’s equal to the difference between premium and regular gasoline, or the difference between regular gasoline and low-octane naphtha sold at distress prices less than the price of unrefined crude oil.

When this is done on a stream that makes up 40% of the U.S. gasoline supply, it amounts to billions of dollars per year of octane destruction.

Refineries adapt

There are many ways refiners are adapting to the octane-sulfur squeeze. One way is to reduce gasoline production; another is to stop feeding low cost, high sulfur feeds to the FCC train. Generally, these adaptive steps restrict the flexibility and productivity of FCC trains to make high-value gasoline from low-value heavy oil, limiting the production of on-spec gasoline and the value addition a refinery can achieve.

In short, the Tier 3 sulfur specification is handcuffing our FCC trains.

This explains why we were told, in the question and answer segment of Valero’s 3rd quarter earnings conference call October 24, 2022, that the only step the Biden administration and refining executives could come up with to reduce fuel costs in the US was to “relax the sulfur spec”. Here is that Q&A:

Connor Lynagh, analyst, Morgan Stanley

I wanted to return to a topic that you mentioned briefly earlier, which is the suggestion that you made to the administration on potential pathways for reducing fuel costs. I’m curious if you could just provide a little color on the things that the industry suggested.

Lane Riggs, Valero Energy President and Chief Operating Officer

Sure. I think — yes, this is Lane. So I think the — there’s two main ones, which was one was increasing or relaxing the sulfur spec on fuels. Many of the US refiners didn’t necessarily invest, in it looks like either making ultra-low sulfur diesel as much as maybe some others, or Tier 3 gasoline. So, consequently, they’re in a posture of having to export some of those — some gasoline and some diesel to markets around the world that can handle the sulfur.

In the next blog in this series, we will discuss what steps can be taken to break free of the Tier 3 chains to increase production and reduce cost of gasoline marketable in the United States.

Recommendation

Every refining executive should have a comprehensive understanding of the technical, regulatory, and economic aspects of Tier 3 gasoline, the sulfur credit program and how they affect your business. Those wanting a quick education on the Tier 3 issue should get the short book, Gasoline Desulfurization for Tier 3 Compliance, which will make you an expert in a day. Once you have become expertly informed of the problem, you can save your team years of research by buying Hoekstra Research Report 8. We saw this problem coming, gathered the required data, ran the simulations and analyzed the results so you and your team can immediately initiate well-informed strategies. The report includes detailed pilot plant and commercial field test data, full detail of sulfur credit pricing, spreadsheet models to help improve gasoline optimization, investment decisions, sulfur credit strategy and refining margin capture in the Tier 3 world.

Don’t get caught panic buying after the credits spike.

George Hoekstra

+1 630 330-8159