Revisiting RIN Cost Pass-through – Part 2 – How is the RIN tax different than a sales tax?

Read other blogs in this series:

- Part 1 – Two Camps

- Part 2 – How is the RIN Tax Different From a Sales Tax?

- Part 3 – The RIN Tax Passes Through Just Like a Sales Tax

- Part 4 – Will the Litigation Ever End?

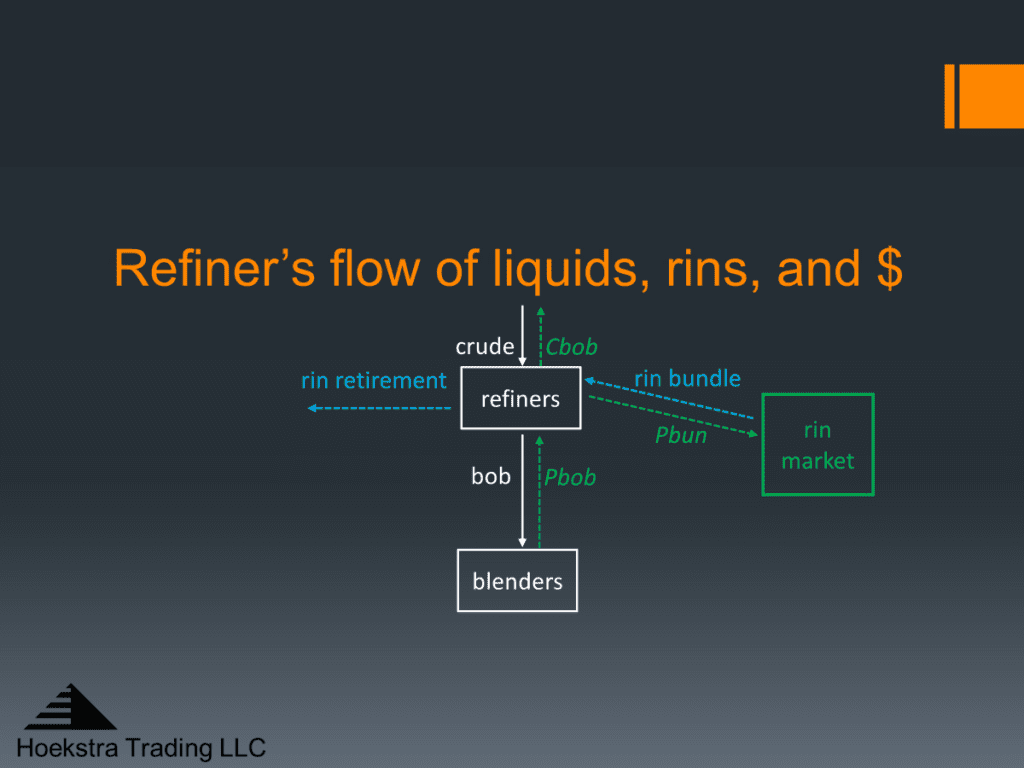

Figure 1 shows refiners buying crude oil and making gasoline called blendstock for oxygenate blending (bob) which is then blended with ethanol to make E10 gasoline (white arrows). For each gallon of bob produced, refiners must acquire a credit called a renewable identification number (rin) bundle and retire it by turning it in to the environmental protection agency (EPA) to prove they have purchased the credit (blue arrows). The refiners’ profit is what they receive for the bob (Pbob) minus their cost to produce the bob (Cbob) minus the cost of the rin bundle (Pbun) (green arrows).

In Part 1 of this series, we described the views of two camps on how the cost of the RIN affects refiners’ profits:

- Camp A, mostly refiners with some economists, consultants, and politicians, says the RIN tax is an extra cost that reduces a refiner’s profit. The refiner sends real cash out the door to buy the RINs with no apparent offsetting revenue. It is a source of large, uncontrollable, highly variable cash expense. How can it not affect their profit?

- Camp B, mostly renewable producers with other economists, consultants, and politicians, says the RIN tax is passed through and recaptured in a higher market price for the bob that offsets the refiners’ cash expense. This is called the pass-through theory.

These contradictory views on the pass-through theory have fueled an 11-year, multi-billion dollar legal dispute that is still in progress today with no end in sight.

What is the basis for Camp B’s pass-through theory?

In competitive markets, participants seek to maximize profit. Suppliers want the price high enough to cover their costs, and higher if possible. Consumers will shop around to spend as little as possible for the product.

If there is a systemic increase in supplier cost that affects all suppliers equally, like a per-gallon tax on supply, profit-seeking suppliers will want to increase their prices to recover that extra cost and sustain their profitability. What will stop them from doing that? The only counter-force to the upward price pressure is if consumers reduce their buying. If that happens, it will limit the ability of suppliers to increase their price. Otherwise, that cost will pass through into the market price of the product.

We know from experience that tax pass-through happens in the gasoline market. When a state sales tax on retail gasoline increases, the retail market price of gasoline goes up and consumers end up paying the tax. That is true even though the tax is imposed on the retail supplier and the retail supplier is the one who actually pays the tax to the state.

Today’s Question

In terms of the pass-through question, how is the RIN tax situation described in Figure 1 different than when a sales tax is imposed on finished gasoline at the retail level?

Recommendation

Hoekstra Trading clients use the ATTRACTOR spreadsheet to compare theoretical and market RIN prices, analyze departures from theoretical value, and identify trading opportunities on the premise RIN market prices will be attracted toward their fundamental economic values.

Get the Attractor spreadsheet, it is included with Hoekstra Research Report 10 and is available to anyone at negligible cost.