The Big Bang Theory Part 1 – The surprising RIN price spike of 2013

See Part 2 of this series

Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) are credits used to certify compliance with the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) which requires certain minimum volumes of biofuels to be blended into fuels sold in the United States. RIN credits come in different categories. One category, code named “D6”, applies to the blending of corn-based ethanol into refined gasoline to make the gasoline-ethanol blends we pump into our cars, SUV’s and pickups. In 2013, the D6 RIN price skyrocketed 100-fold in one of the most extreme cases of panic buying in any major commodity market in history. This blog examines that event and raises two questions:

- How did it happen? and

- Could it happen again?

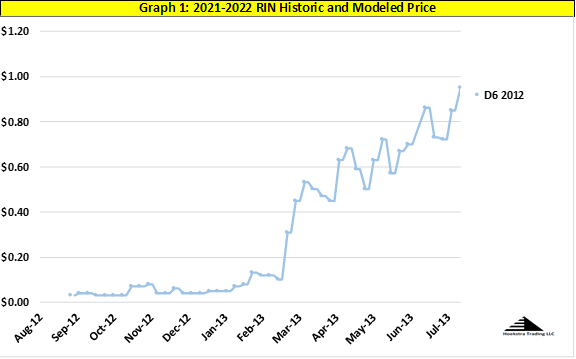

From early 2012 to mid-2013, the D6 price rose 100-fold, from 1 cent to 1 dollar per RIN, with most of that gain coming in a several-week period in the spring of 2013.

We must emphasize the magnitude of this spectacular price rise. It was not 100%, or even 10-fold (which is 1000%), it was 100-fold. It is hard to find a buying panic like this in the annals of major commodity trading. Even the infamous gambler and banker John Law narrowly escaped public hanging after being blamed for much smaller losses stemming from the introduction of paper currency and national credit notes in France in 1718.

To our knowledge, no one has yet been threatened with execution over RINs (though some have been jailed). But the 2013 D6 RIN price explosion rocked the fuels industry. Loud objections, congressional hearings and finger-pointing among refiners, biofuel producers, bankers, accused RIN hoarders, and politicians rang through the corn and oil ecosystem. That’s because, with this price spike, refiners, who naturally tend to be short RINs, were suddenly paying $14 billion per year for them. This New York Times article from November 2013 is a good report on the frenzy set off by the D6 RIN price explosion, 300 years after the near hanging of Mr. Law.

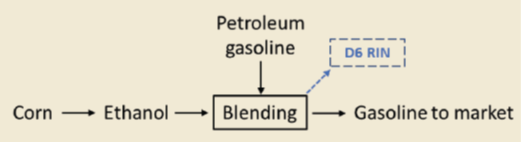

The price spike occurred because ethanol use, which had been increasing steadily through 2010, 2011, and 2012, reached the 10% maximum that can be blended into “E10” gasoline. Before hitting the 10% ceiling, the D6 ethanol production pathway, illustrated in Figure 2, had been running on autopilot for years — feeding corn, making ethanol, blending it with refined petroleum gasoline and selling the blend as E10 gasoline.

Through 2012, the amount of ethanol in gasoline had been increasing gradually and the ethanol was serving as an economical octane booster. This was a profitable production pathway for everyone involved. Farmers, ethanol producers, refiners, and blenders were all content with their profitable E10 businesses.

But the renewable fuel mandates for future years demanded ever-increasing biofuels volumes. By 2013, the use of ethanol in E10 had grown to its maximum 10%, or 13 billion gallons per year (this maximum became known as the “blend wall”), while the biofuels mandates effectively dictated a minimum 13.8 billion gallons per year. We had a 13.0 maximum and a 13.8 minimum.

In Washington DC, where things are done on paper, it is possible to have a maximum that is below the minimum. But that doesn’t work in real life. Something would have to give.

The ensuing controversy came to be known as “RINsanity”. In November 2013, a leaked EPA proposal signaled lenience on the ethanol volume mandate, suggesting EPA might lower the mandate to below the blend wall limit and solve the problem. That triggered a fast crash of RIN prices. Then EPA failed to issue its volume mandates on time for 2014, which left everyone guessing what biofuel demand would be. It was not until May, 2015 that EPA issued proposed RFS mandates for 2014-2016. That proposal was also seen by the market as accommodating to refiners’ objections and was accompanied by another sharp fall in RIN prices. The chaos continued and didn’t subside as we approached the 2016 election (nor did it afterward).

Later, commenting on this phase of RIN history, Bruce Babcock, public policy professor at University of California Riverside weighed in, suggesting the Obama administration was caving to unfounded fears that high RIN prices would bankrupt refiners and cause our fuel supply to dry up, saying in a comment in an industry journal:

At a critical time, after RIN prices dramatically increased to reflect the expected wide gap between supply and demand prices for biofuels, the Obama EPA paused. One plausible explanation for this pause was that administration economic and political advisors believed oil industry arguments that high RIN prices would put the US refining industry at financial risk and threaten the US fuel supply.

Bruce Babcock in American Journal of Agricultural Economics, March, 2020

1.1 Possible solutions

Everyone knew the blend wall was coming. So how would we get to 13.8 billion gallons of ethanol when 13.0 was the maximum that could go into E10 gasoline?

One way was to increase production of E85 gasoline which is a D6 biofuel blend with a higher ethanol percentage for flex-fuel vehicles designed to use it. Ethanol in E85 is not limited by a blend wall. Blending more E85 would generate more D6 RINs and solve the blend wall problem. But this was an infeasible solution because of inadequate E85 infrastructure and end-user demand.

Another solution was to lobby, and/or sue EPA to force reduction in the 13.8 billion gallon mandate. That solution was pursued vigorously but failed.

A third solution would take advantage of RFS rules about a different category of biofuels called advanced biofuels. By rule, if advanced biofuels are produced in quantities that exceed the advanced biofuels mandate, those extra advanced gallons count toward meeting the D6 mandate. This third solution, the biodiesel solution, is what actually happened.

The biodiesel solution will be explained in the 2nd episode of this series. For today, the critical point is that, in 2012, knowledgeable parties recognized that, short of a regulatory or legal solution, it was inevitable the price of the D6 RIN would increase. The most likely solution was to produce more biodiesel, which, for reasons to be covered in Part 2 of this series, would necessarily come with a higher RIN price.

Among those who predicted the inevitable D6 RIN price increase were University of Missouri researchers whose December, 2012 article “A question worth billions: why isn’t the conventional RIN price higher?” predicted the D6 RIN price would need to rise to $0.60 to balance 2013 RIN demand and supply, and stated:

Biodiesel adoption suffers no similar blend wall constraint at 10% of use. However, biodiesel RIN prices as of mid-November 2012 are in the $0.50-0.60 range – more than ten times the conventional RIN price – and have been higher. If biodiesel is used because the conventional RIN price rises to this level, then this outcome might be identical to outcome 1,

Here, “outcome 1” refers to the D6 price rising to $0.30-0.60 or more.

Others, including RBN’s March 2013 blog Will RIN and Stimpy Dodge the Ethanol Blend Wall in 2013?, were working the numbers to anticipate how the blend wall would affect D6 RIN supply and demand as the day of reckoning came:

For 2013 at least, the question remains — are there enough RIN credits available in the market from 2012 to meet the ethanol targets this year? A lot of this analysis is hypothetical because we don’t know the exact number of credits or the shortfall of ethanol after we hit the blend wall. Recent scholarly research on the topic by the University of Illinois Department of Agriculture and Consumer Economics (published here) suggests the stock of RIN credits at the start of 2013 was 2.6 billion gallons (170 Mb/d), which will be depleted to 1.2 billion gallons (78 Mb/d) by the end of the year.

RBN Energy blog, “Will RIN and Stimpy Dodge the Ethanol Blend Wall in 2013?” March, 2013

The University of Illinois group, headed by Scott Irwin, was writing frequently about the theory of RIN pricing and the price implications of the impending collision with the blend wall. Clearly, those implications were accurately foreseen in 2012 by those with deep understanding of the RIN credit system, and by those who dug deep enough to discover them.

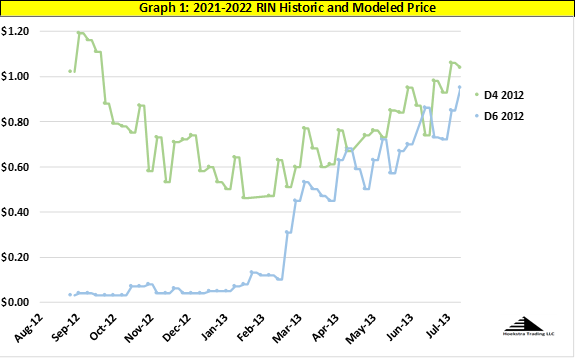

When the biodiesel solution kicked in, the D6 RIN price snapped up to just below the D4 RIN price and the two RIN prices began trading in tandem, as shown in Figure 3:

This is exactly the outcome predicted by the University of Missouri and University of Illinois groups, and others who understood the inner workings of the RIN system.

Why was the price spike so abrupt? In particular, why wasn’t there more D6 RIN buying in 2012 in anticipation of a coming train wreck? The most likely reason is the biggest RIN stakeholders lacked sufficiently deep awareness and understanding of the workings of the complex RIN credit system.

And that suggests that, in this day when complex credit systems are driving the fuels industry, it could easily happen again.