RINatomy Part 3 – The RIN As A Mandate

RINs come in different categories, some of which have associated with them a mandated annual volume of biofuel that, by law, must be supplied to the U.S. market.

Anatomy noun, anat·o·my ə-ˈna-tə-mē a study of the structure or inner workings of something

Read other blogs in this series: RINatomy:

- Part 1 The RIN As A Subsidy

- Part 2 The RIN As A Tax

- Part 3 The RIN As A Mandate

- Part 4 The RIN As An Asset

- Part 5 The RIN As A Contingent Claim

The D4 RIN is designed to draw bio-based diesel into the U.S. diesel fuel supply. As described in Part 1, it does this by functioning as a variable-rate coupon that discounts the cost of bio-based diesel to subsidize use of bio-based diesel that would otherwise not be economically competitive with petro-based diesel.

The D4 RIN is also designed to draw in enough dollars to pay for that subsidy. As described in Part 2, It does this by functioning as a variable-rate tax that increases the price of petro-diesel which raises just enough dollars to fund that subsidy.

A Cross-subsidy

So the RIN is both a subsidy and a tax. In economics, this is called a cross-subsidy. An example is when a member of a professional society is charged a higher membership price to fund lower-price student memberships. The amount of the “tax” on professional members’ fee is just enough to cover the subsidy provided to the student members.

A cross-subsidy is a clever way to draw in and fund something that would otherwise be excluded because of high price.

A Mandate

As if that were not enough, the D4 RIN is also charged with responsibility to make sure the quantity of bio-based diesel drawn in is exactly the specified minimum mandated quantity.

the D4 RIN is also charged with responsibility to make sure the quantity of bio-based diesel drawn in is exactly the specified minimum mandated quantity.

3 equations, 3 unknowns

There are many kinds of environmental credits. Other than the RIN, I am not aware of any that is expected to perform all three of these jobs simultaneously, to be a coupon that provides a subsidy, a tax that funds the subsidy, and a flow controller that delivers exactly the specified number of subsidized gallons, all at once.

The RIN is a coupon that provides a subsidy, a tax that funds the subsidy, and a flow controller that delivers exactly the specified number of subsidized gallons, all at once.

How does the RIN do it?

By design of the system, the RIN’s price is driven by competitive market forces to the single value that satisfies all three requirements simultaneously. Under the assumption the fuels markets are competitive at all levels of the supply chain, that single value is the number we have named “D4T”, meaning D4-Theoretical price.

Hoekstra’s D4T is the world’s first licensed theoretical value of an environmental credit.

Hoekstra’s D4T is the world’s first licensed theoretical value of an environmental credit.

Misunderstanding

How the RIN performs this 3-part feat is widely misunderstood and that misunderstanding is the root cause of a 10-year, billion dollar legal battle that is still being fought today with no end in sight.

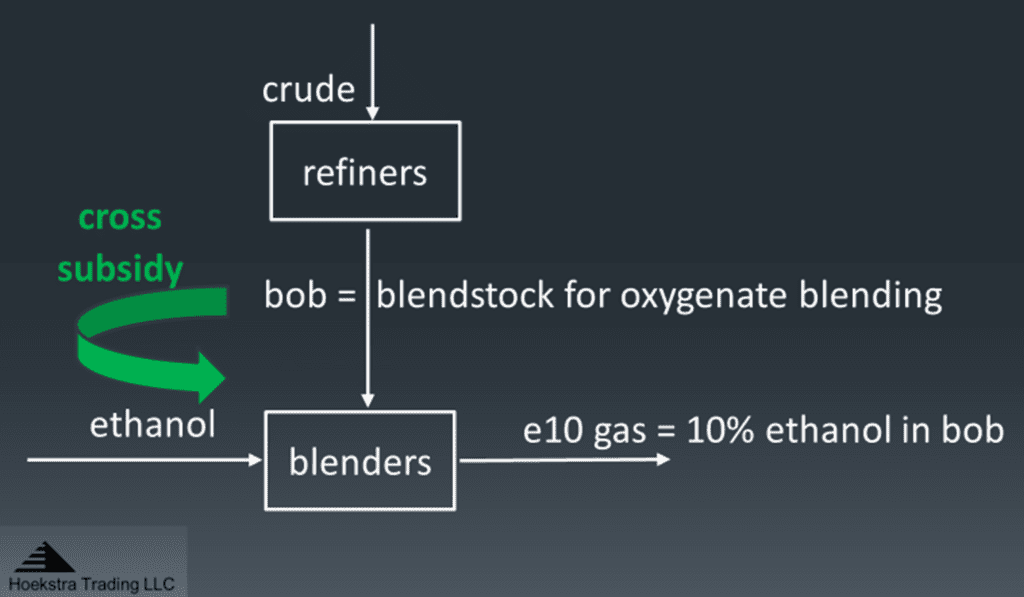

An especially confusing point is the cross-subsidy aspect. The cross-subsidy is depicted schematically in Figure 1 which shows the flow of the streams involved in producing the 10% ethanol gasoline blend called e10 that we pump into our cars.

Figure 1 flow of streams (white) and RIN value (green) in the blending of 10% ethanol with 90% bob. Source: Hoekstra Trading LLC

In this process, the petro-gasoline called blendstock for oxygenate blending (bob) is produced by refiners and blended with 10% ethanol. The RIN tax is imposed on refiners and, in competitive markets, passes through to increase the market price of bob (like a sales tax does, see part 1). The blender pays the tax, in the form of a higher market price for bob, to the refiner and (by rule) gets a coupon (RIN) with the ethanol he buys for use in fuel. The blender redeems the coupon by selling it for cash which effectively gives him a discount on the ethanol, offsetting his higher cost for bob.

The outcome is the displacement of a gallon of bob with a gallon of (higher cost) ethanol in the fuel supply, which has been funded by a cross-subsidy as indicated by the green arrow.

That is how the clever and confusing cross-subsidy works. Notice that all three entities in the diagram come out whole: The refiner pays the tax and, as with a sales tax, gets that back in the form of a higher market price for bob. The ethanol supplier receives the same market price for ethanol as he gets for sales to the non-fuel ethanol market, and the blender pays a higher price for bob which is offset by cash received when redeeming the coupon that came with the ethanol.

The net outcome for the market as a whole is that an ethanol supplier has captured a gallon of market share from the bob suppliers he would not otherwise have.

Hoekstra Trading’s Research Report 10, and my 4-part series titled Misunderstanding, published 2 years ago on the RBN Energy Daily Blog, gives more detail on how the cross-subsidy works and address six prominent points of contention that underly the 10-year legal battle, all of which stem from misunderstanding of the cross-subsidy:

- Contention 1. Paying for RINs is an extra cost that reduces a refiner’s profits.

- Contention 2. Some refiners don’t have pricing power to be able to pass through their RIN costs.

- Contention 3. Cashing out the RIN subsidy is a windfall profit for the blender.

- Contention 4. An integrated refiner gets RINs free while a non-integrated refiner must buy them

- Contention 5. Consumers pay more for E10 because of the RIN tax.

- Contention 6. High and volatile RIN prices indicate the program is dysfunctional.

The next episode will cover the RIN as a bankable asset.

RINatomy

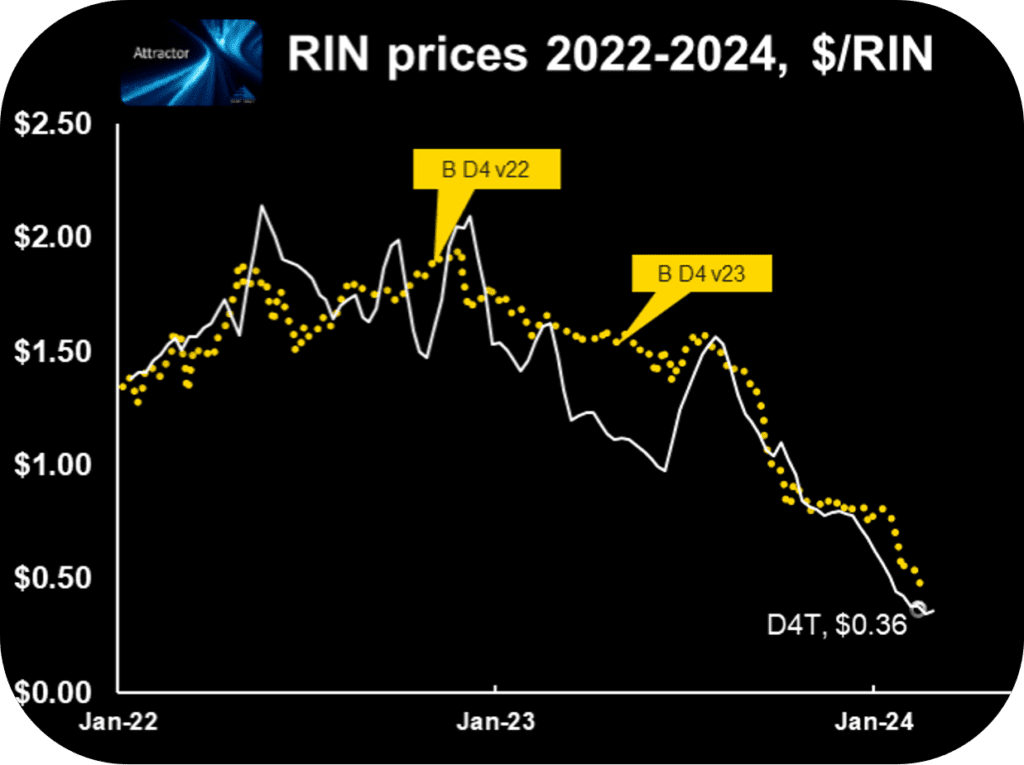

This blog series, titled RINatomy, covers the basic structure and inner workings of the RIN price control system, something I learned about 3 years ago that helped me and Hoekstra Trading’s clients get a grip on what drives the otherwise bewildering behavior of RIN prices, and to then effectively track, interpret, and anticipate RIN price behavior using the Attractor spreadsheet which compares D4 RIN market prices to a theoretical value called D4T which is calculated using economic fundamentals and is the world’s first licensed theoretical value of an environmental credit.

Attractor update

The Attractor spreadsheet shows the D4 RIN market price (gold points) and the “D4T” theoretical value (white line and open white data point) updated through last Friday. The theoretical value of a hypothetical D4 RIN with 1 year remaining life (“D4T”) is $0.36 which is up 3 cents from last week.

Hoekstra Trading clients use this spreadsheet to compare theoretical and market prices, analyze departures from theoretical value, and identify trading opportunities on the premise RIN market prices will be attracted toward their fundamental economic values.

Get the Attractor spreadsheet, it is included with Hoekstra Research Report 10 and is available to anyone at negligible cost!

George Hoekstra george.hoekstra@hoekstratrading.com +1 630 330-8159