Baby, The RIN Must Fall Part 1 – What’s Behind The Chatter About RIN Prices Crashing To Zero?

The Renewable Identification Number (RIN) is an environmental credit that functions as a subsidy to force renewable fuels like ethanol and soybean oil into gasoline and diesel fuel. Recently, chatter has bubbled up across the RINs ecosystem that RIN prices might crash to zero in the near future. That would be headline news that would shock the fuels markets. This blog explains what’s behind this RIN price crash chatter.

This post was published on the Hoekstra Trading blog June 13, 2023, and an edited version appeared as the RBN Energy Daily Blog July 5, 2023 . Read other blogs in this series Baby, The RIN Must Fall –

- Part 1 What’s Behind The Chatter About The RIN Price Crashing To Zero?

- Part 2 Will a RIN Price Crash Make a Mess In The Renewable Diesel Market?

- Part 3 The Odds and Timing Of A Potential RIN Price Crash

- Part 4 D4 RIN Nosedives, Triggering a Flurry of Market Reactions

RINs are a feature of the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) which requires certain minimum volumes of biofuels to be blended into fuel sold in the U.S. RINs come in different categories with different code names. This blog series focuses on the D4 RIN, which applies to bio-based diesel fuels made from soybeans and other bio-feedstocks.

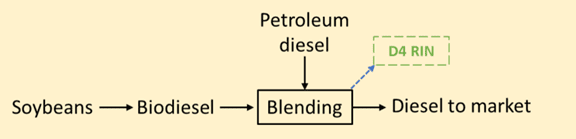

The D4 RIN (see Figure 1) is a virtual coupon that comes attached to each gallon of biodiesel. It is detached by a blender when that gallon is blended with conventional petroleum diesel for use as fuel. The blender then redeems the coupon by selling it to petroleum fuel suppliers who are obligated to meet a biofuel supply quota each year. Through competition in the fuels supply chain, the RIN value winds up subsidizing the production of biodiesel gallons that would not otherwise be economically justified. See our 4-part blog series, The RIN is a tax and a subsidy that forces renewables into fuels for full explanations how this clever price control system works.

Figure 1 Flow diagram for biodiesel supply to the U.S. diesel market

Through competition in the fuels supply chain, the RIN value ends up subsidizing the production of biodiesel gallons which would not otherwise be economically justified.

Two types of bio-based diesel

Figure 1 applies to a type of bio-based diesel commonly called biodiesel. A second type of bio-based diesel is commonly called renewable diesel and it also comes with a virtual D4 RIN. Both types are derived from oxygen-containing organic compounds called triglycerides that make up vegetable oils and animal fats in bio-feedstocks. The biodiesel production process reacts those triglycerides with methanol to make oxygen-containing fuel molecules called fatty acid methyl ester (FAME), which is commonly called “biodiesel”, as in Figure 1. By contrast, the renewable diesel process reacts the triglycerides with hydrogen (instead of methanol) to make oxygen-free fuel molecules identical to those in conventional diesel fuel, releasing oxygen in the form of water (H2O) in the process.

To clarify the distinction between the two types, we will call the first type “FAME biodiesel” and the second type “hydrogenated renewable diesel”.

The key difference in the two types of product is that FAME biodiesel still has oxygen atoms embedded in its molecules. That limits its use as a diesel fuel substitute and is why it is typically blended with conventional petroleum diesel before being sold as fuel.

The key difference in the two types of product is that FAME biodiesel still has oxygen atoms embedded in its molecules.

Repurposing refinery hydrogenation reactors

Hydrogenation is the most widely used process in petroleum refining. Consequently, it has been relatively easy for refiners to produce large volumes of hydrogenated renewable diesel by repurposing existing refinery hydrogenation units.

Since 2019, U.S. nameplate production capacity of hydrogenated renewable diesel has grown from 0.6 to 2.6 billion gallons/year. In December 2022, hydrogenated renewable diesel was being produced at a rate of 1.8 billion gallons/year at sixteen plants in the U.S., mostly in reactors that were previously producing clean diesel and clean gasoline from petroleum-derived feedstocks in refineries. University of Illinois research indicates hydrogenated renewable diesel production capacity is on pace to grow to 4.2 billion gallons/year by 2023, and 6.0 billion gallons/year by 2025.

University of Illinois research suggests hydrogenated renewable diesel production capacity is on pace to grow to 4.2 billion gallons/year by 2023, and 6.0 billion gallons/year by 2025.

Market share is shifting

While production of hydrogenated renewable diesel has been racing forward, the FAME biodiesel business, which was supplying 95% of our bio-based diesel in 2013, has stalled in its tracks. It is sputtering around 1.8 billion gallons/year and falling, and has now been surpassed by its startup rival, hydrogenated renewable diesel.

Why is hydrogenated renewable diesel lapping FAME in the bio-based diesel supply race?

Economies of scale is one reason. The smallest hydrogenation units produce about 100 million gallons per year, which is the size of the biggest FAME biodiesel plants.

The ability to drop hydrogenated renewable diesel directly into large scale transportation systems including pipelines is a similar advantage for hydrogenated renewable diesel.

From the standpoint of competitive costs, it is not surprising that hydrogenated renewable diesel plants are rapidly displacing FAME biodiesel plants on the supply side of the ledger. In an ideal world where free markets ruled, it would seem that hydrogenated renewable diesel would continue gaining market share and growing profits at the expense of higher cost FAME biodiesel.

But refiners should remind themselves that free markets don’t rule the world of fuels today — and that if they did, the demand for both types of bio-based diesel would most likely be zero. That’s because both types of bio-based diesel are more expensive than petroleum diesel, and demand for them only exists because of government (RFS) minimum quotas, supported by tax credits and various state subsidies. In other words, this is a government-controlled market.

This is a government-controlled market.

2013 – coming under the grip of government control

Refiners first felt the strong grip of the government RFS mandates in 2013. Before then, refiners could meet most of their RFS volume obligations by blending ethanol into gasoline. That was painless because ethanol provided a valuable octane boost, enough that ethanol was earning its way into the gasoline supply chain on economic grounds, even without a subsidy. At that stage, it was very much like a free market.

But in January, 2013, the market ran full speed into a constraint commonly called the “ethanol blend wall”. The blend wall was actually two constraints; one was a technical constraint saying no more than 13 million gallons/year of ethanol could be blended into the U.S. fuel supply. The other was a government (RFS) constraint saying no less than 13.8 billion gallons of ethanol/year must be blended into the fuel supply. You can’t simultaneously blend less than 13.0 and more than 13.8 of anything into anything.

The solution to this contradiction came via the “nesting” provisions of the RINs system which led to refiners being blindsided by $billions/year of unanticipated costs to buy RIN credits right after their price had increased 100-fold. See our RBN Energy Big Bang Theory blog series for an explanation of this threshold 2013 event and its consequences.

The 2013 Big Bang is pertinent to today’s topic because the possibly imminent RIN crash event would be much like replaying the Big Bang in reverse 10 years later, in the sense that refiners would be released from the government control that first gripped them in 2013. Since 2013, the bio-based diesel market has been bound in that grip, during which the RFS mandates determine demand for the product, the D4 RIN is the instrument to enforce that mandate, and the D4 RIN price fluctuates to stay equal to the per-gallon subsidy needed to match market supply with the required demand. (see our RBN Energy drill down report: Land of Confusion for full explanations of how this cleverly-designed price control system works).

the possibly imminent RIN crash event would be much like replaying the Big Bang in reverse 10 years later

2023 – Return to free market control?

Today’s chatter is that rapid growth of hydrogenated renewable diesel has drawn the bio-based diesel market to the edge of another threshold event that would release it from the grip of the binding RFS government mandate and place it back into control of the free market. That threshold is where the total supply of bio-based diesel grows to the point where it equals the minimum volume set by the renewable fuel standard. The previously cited University of Illinois research has gathered the data and done the necessary RIN accounting to show that point is imminent.

When that threshold is crossed, by definition, no RIN subsidy will be needed to meet the minimum supply mandate. And, as explained in our RBN Misunderstanding series and Land of Confusion drill down report, when no subsidy is needed, the price of the RIN goes to zero – and that scenario is what’s behind the RIN price crash chatter.

when no subsidy is needed, the price of the RIN goes to zero

What would be the consequences of crossing that threshold? We don’t claim to know the answer, but will address that question in Part 2 of this series.

Recommendation

Anyone with a stake in RINs pricing and economics should get Hoekstra Research Report 10 which includes this Hoekstra IMS RINs pricing spreadsheet that accurately calculates theoretical RIN prices, tracks actual prices, and predicts how RIN prices will change with the variables that affect them. Why not send a purchase order today?

George Hoekstra george.hoekstra@hoekstratrading.com +1 630 330-8159

Anyone with a stake in RINs pricing and economics should get Hoekstra Research Report 10